Those who have been following the Philippine transport soap opera involving the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board and all the transport network companies wishing to do business in the country, should be pretty familiar with the basic narrative: TNCs (particularly Grab and Uber) came in and became hugely successful, LTFRB entered the picture wielding its hammer of regulations, TNCs started having problems meeting rider demand.

To be fair, much of the legal tussle between the controversial government agency and the TNCs stemmed from the latter’s stubborn refusal to submit themselves to authority, resulting in penalties and the full (read: faultfinding) attention of the regulators. Of course, nobody really wins against the government. When the smoke cleared, the LTFRB had significantly reduced the number of Transport Network Vehicle Service cars legally allowed to serve the riding public. By January 2018, that number had gone down from an estimated 125,000 vehicles (many of them admittedly not possessing proper LTFRB documentation) to a “common supply base” of just 45,000 cars (adjusted to 65,000 in February). And Grab—criticized for its “poor” service or inability to adequately serve ride bookings—now wants to give people a quick history lesson as to what led us to this whole ride-hailing mess in the first place.

Here, then, is “Philippine Ride-Sharing Saga 101,” brought to us by Grab.

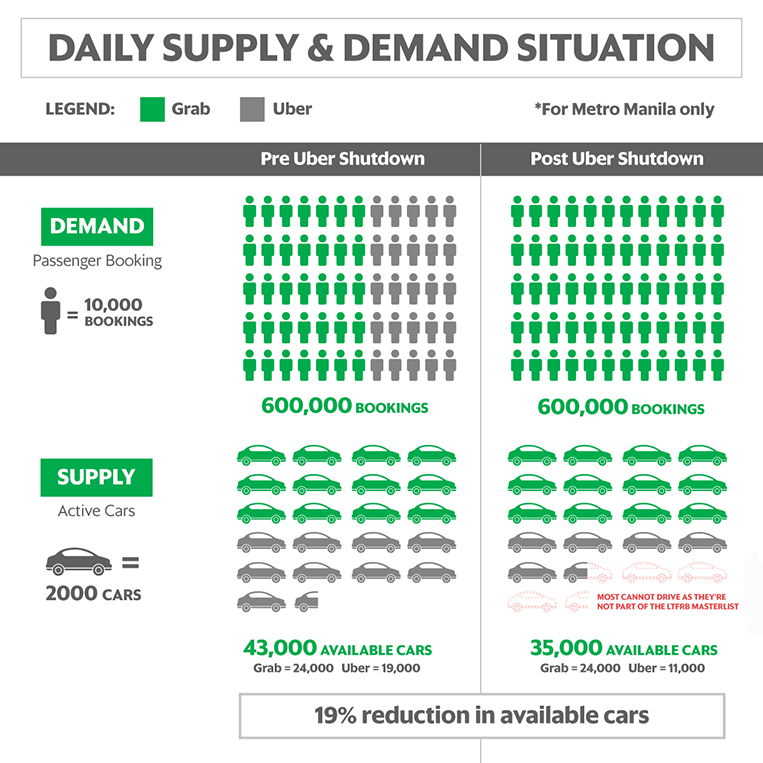

According to Grab, at the beginning of the year, after the LTFRB had imposed the vehicle supply cap, there were only 43,000 available TNVS cars—24,000 with Grab and 19,000 with Uber—left to serve an average of 600,000 ride bookings per day. When Grab bought out Uber’s Southeast Asian operations, forcing the latter to pull out of the market, the number of available TNVS cars further went down to 35,000—6,000 Uber drivers were discovered to not be included in the LTFRB’s master list, and 2,000 (also Uber drivers) simply decided not to cross over to Grab. That’s a 19% reduction in available TNVS cars from what had already been a substantially diminished pool.

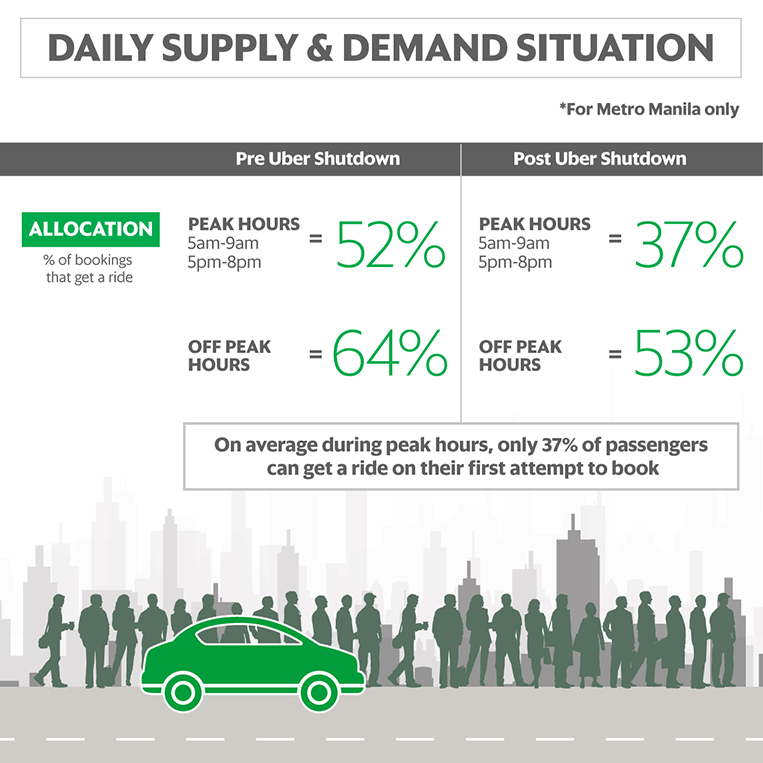

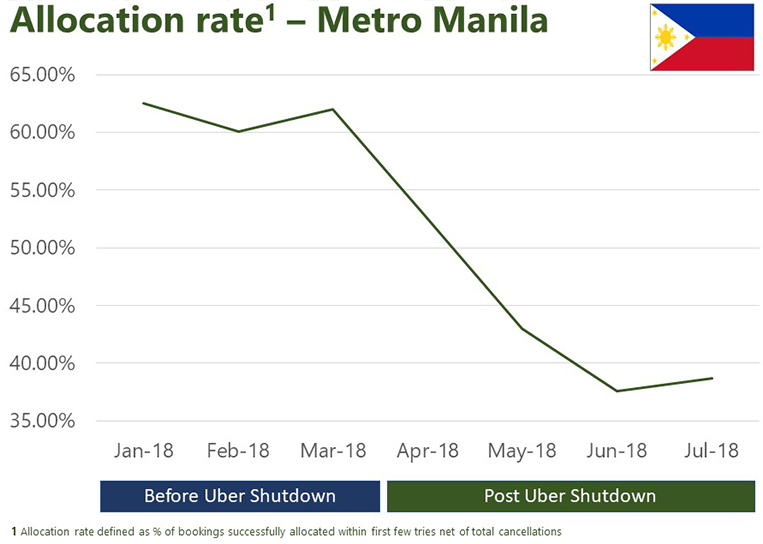

The result, at least based on figures provided by Grab, has been abysmal. Before Uber’s pullout, Grab says it had an allocation of 52% during peak hours and 64% during off-peak hours. Which means the company was able to serve 52% of bookings (or ride requests) during peak hours and 64% during off-peak hours. After Uber’s departure, Grab claims those numbers plummeted to 37% during peak hours and 53% during off-peak hours—thanks to the deactivation of 6,000 Uber cars and the voluntary abdication by 2,000 Uber operators and/or drivers.

In essence, Grab is telling us: “Don’t blame us for our inability to satisfy your transport needs; our hands are tied by the woefully insufficient vehicle supply.”

Moreover, Grab is pointing at the recent suspension of its sneaky P2-per-minute charge as the main reason its drivers have suffered financially, causing many of them to quit altogether. According to the ride-sharing firm, the number of its online drivers declined by 6% from April to July. “Low income has affected driver behavior because they are left with no option but to make decisions that enable them to make ends meet,” Grab argues in a statement sent to VISOR.

So, not only does the Philippines supposedly now have the lowest ride allocation rate among all Grab markets in Southeast Asia at 40%, the average pick-up time has also gone up from a January-to-March average of six minutes to a July median of eight minutes. You’re not imagining things if you now feel like your Grab ride is becoming more and more difficult to book, and the waiting time for its arrival is becoming longer and longer.

Grab now wants to give people a history lesson as to what led us to this whole ride-hailing mess in the first place

“The Philippines, despite being the first country to legalize ride-sharing in Asia in 2015, is facing a big setback because of the supply crisis,” Grab Philippines country head Brian Cu is quoted in the statement as saying. “We acknowledge and thank the LTFRB for allowing 10,000 TNVS slots, but this is just a first step. More should be done to end the wait of passengers and drivers. We urgently request the LTFRB to replace inactive vehicles with active ones ready to serve the riding public. We also appeal for the increase of the common supply base to 80,000 vehicles, which is equivalent to 65,000 active vehicles anyway.”

Cu would also like for the regulators to review the ride-sharing demand quarterly, “consistent with their earlier pronouncements.”

While we’ve been vocal about our support for proper government regulation when it comes to these transport network companies, we also feel that the needs of the general riding public should be prioritized over all other issues—political or otherwise. Penalize TNCs when they err, yes, but also make it possible and realistic for them to provide quality service. Grab, let’s be clear, has had several missteps in its young existence in the country, but now the LTFRB must get to work in addressing the company’s seemingly legit concerns. Continue procrastinating and the suspicion that the agency is favoring certain players in the TNVS industry will only grow stronger.

Comments