MG Philippines recently created a bit of a PR boo-boo when the distributor posted on its Facebook page that its cars are “only for the young,” telling potential buyers above the age of 40 to go elsewhere. Most people initially thought that the post may have been a mistake or the work of a rogue intern on weekend duty, but then company president Morgan Say came out and confirmed that the brand wants to market itself to young millennials, and not to old farts with jobs, money and hence the means to actually buy a brand-new car.

While the approach of MG Philippines caused some head-shaking and raised eyebrows, it is by no means the first and only public relations mishap by a car brand. Here, we list four common mistakes—with classic examples—automotive firms can make when marketing their products.

1. Coming out with an advertising campaign that doesn’t make sense. French manufacturer Renault had high hopes for the 14 compact hatchback when it launched the car in 1976, but things didn’t quite go according to plan, and this was mostly down to the terrible advertising campaign the company came up with. For some unknown reason, Renault compared the car to the shape of a pear, as if that particular fruit had some sort of positive attributes applicable to automobiles. The public didn’t get it, and as the 14 also corroded faster than a politician’s morals after an election win, the unlucky little runabout was soon known as the “rotten pear.” Even today, the term La Poire (meaning “The Pear,” but also French slang for a person who is easily fooled) still refers to this car.

TIP: This usually happens when you hire a non-car person to head your marketing department. We don’t care if an executive has won all kinds of marketing awards, but if he or she doesn’t understand or isn’t passionate about cars, the person will never get the language that will resonate with car buyers. Then again, it is also wrong to entrust your brand to a hardcore car enthusiast without a solid marketing background. That, too, could be a disaster. Fortunate are the carmakers that have marketing executives who also happen to be genuine petrolheads.

2. Failing to study a foreign market and how to sell a product there. When Mitsubishi branding executives were looking for a strong name to bestow upon their new SUV model in the early ’80s, christening it after a type of cat associated with the wilderness of Patagonia seemed like a great idea. Tough, agile and able to handle rough terrain, the Leopardus Pajeros, also known as the Pampas cat, sounded like a perfect name source, and so the Pajero was born. Unfortunately, the brand had overlooked that “pajero” is a rather rude slang term in Spanish, referring to a gentleman who likes to indulge in self-love a lot, and not in a good way. Once they realized the oversight, the car was marketed under a different name in certain countries. And that’s why we also know it as the Montero.

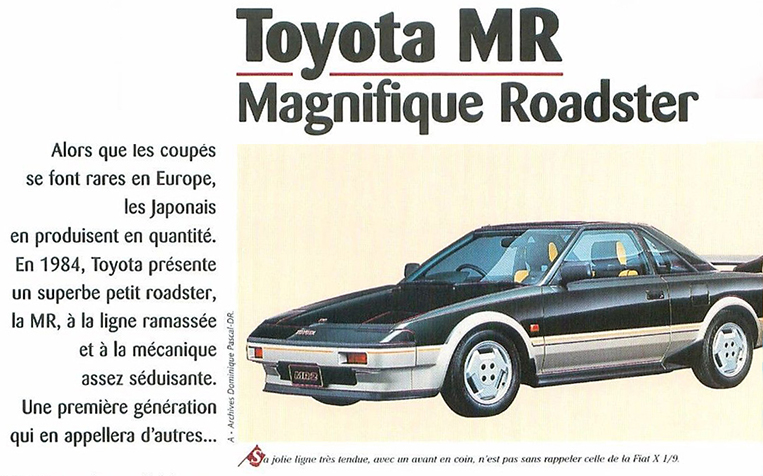

Meanwhile, it’s not only French brands that get it wrong in France, as Toyota found out when it initially launched the MR2 in the country. While the name seemed innocent enough, saying “M-R-Deux” quickly in French makes it sound a lot like “Merde,” and that’s not a French word you want to use when calling your car. Instead of running the risk of having its sports car forever tied to poo in France, Toyota quickly renamed it to just “MR.”

TIP: It’s never easy naming cars. What sounds like heaven in one market could ring like hell in another. By the same token, it’s never easy plotting a global marketing campaign in different countries. Marketers always need to be sensitive to variances in culture, politics, even religion. Even a well-meaning promo might backfire if it violates, for instance, a sacred tradition in the country it is being aimed at.

3. Overdoing brand positioning or exclusivity. The late Tony Crook, during his reign as the owner of boutique manufacturer Bristol Cars, was a PR disaster who committed commercially questionable acts that ultimately contributed to the company running into financial difficulties. Crook was a no-nonsense British gentleman who had served his country as a fighter pilot in World War II, and became a racing driver afterward. His company only had one showroom, on Kensington High Street in London, and it was Tony himself who usually manned it. Under his watch, buying a Bristol was a complicated exercise. Because the only way to acquire one of the brand’s cars was to get Tony’s approval. If he didn’t like you—for whatever petty reason—he simply wouldn’t sell you a unit. He also never lent cars to the press and was known to check the newspaper for Bristol owners who were selling their pre-owned cars, whom he would then phone up and ask why they were unloading their wheels.

TIP: While exclusivity is good, no straight-thinking businessperson can afford to be too choosy. We’ve heard stories of wealthy customers walking into showrooms of luxury car brands wearing only shorts and flip-flops—and then paying in cash (yes, cash). The thing is, you can’t box people into stereotypes and alienate those that don’t fit your mental picture of your “target market.” Sometimes those who have the real capability to buy an expensive car look like nobodies, while those who can’t even afford the down payment walk around like VIPs. Best to be nice to everyone. You never know who might pay your store a visit one of these days.

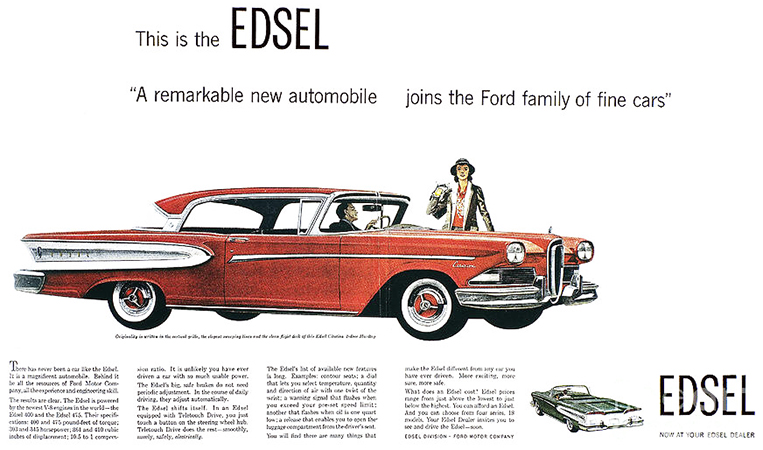

4. Ignoring market research and trends. One of the biggest commercial failures to ever happen in the automotive world, Ford Motor Company’s Edsel sub-brand in the late ’50s was a shining example of how not to design and market cars. Development on the Edsel automobile started in 1955, and to be sure that the new model would fulfill all the requirements of Ford’s loyal customer base, the company carried out comprehensive research, including exhaustive polls asking car shoppers what they were looking for in a new vehicle. Ford then took all that valuable market research data and threw most of it away in a spectacular case of “we know better than anyone what our customers want.” The marketing department also overpromised and built up immense expectations with a yearlong campaign prior to the launch. When the car was finally unveiled, it turned out to be ugly, unreliable and way too expensive. As a result, nobody really bought it and Ford lost a reported $250 million.

TIP: It’s never a good idea to believe that you know better than the customer. In a perfect world, we would all be Steve Jobs dictating to the market what we believe it wants, instead of being told how to develop and package our products and services. But we don’t live in a perfect Apple universe. Customers are fickle. Their tastes change. Their requirements vary from person to person. You simply cannot leave product development to your gut feel just because you think you’re a “maverick.” There’s a reason companies spend a fortune on market research and focus groups. Take customer feedback seriously. That said, it doesn’t mean you can’t innovate. You can—and should—but make sure the innovation is born out of a sound customer-oriented plan and not merely a shallow desire to be “different.”

Comments