Nostalgia is priceless. A colleague wrote a column about this theme, and how peoples’ yearning for the past drives up the prices of commodities—sometimes to unreasonable levels.

I myself am a sucker for vintage stuff whether they are cameras, watches, cars or bicycles. And that’s why I couldn’t resist getting a Bridgestone Eurasia when the opportunity came through an online friend.

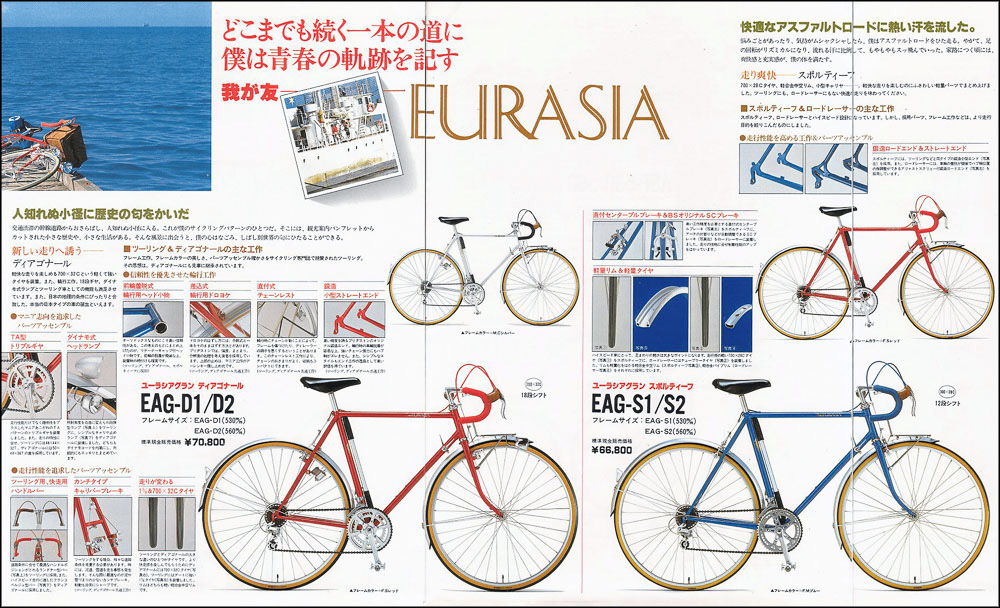

The Eurasia was only sold in Japan from the late 1970s to the early 1980s, making it a bona fide JDM piece. Judging from the covers of cycling publications of the time, bike-touring was a popular hobby, which explains why Bridgestone released mass-market models of randonneuring bikes.

Pardon my French, but randonneuring is a noncompetitive cycling activity where participants travel long distances, self-supported. Its rich history can be traced to the Paris-Brest-Paris event and frame makers such as Alex Singer and René Herse.

Despite all the knowledge and experience I’ve gained from modifying bicycles, working on this project proved to be a massive headache. The goal was to modernize the classic bike as much as possible for convenience’s sake, while retaining its character. And this repeatedly challenged my patience, just as much as my budget.

The frame is made of chromoly steel and has features that distinguish vintage bicycles: a horizontal top tube, a curved fork, a lugged frame, and a quill stem. True to its function as a touring bike, it comes with wide tire clearance (as much as 700c by 38mm without fenders), provisions for a front rack and fenders, and a chain rest on the seat stay.

When dealing with old bikes, finding parts is difficult. I had to either scour through Facebook Marketplace and hoard them from online sellers, or resort to purchasing expensive retro-looking components from high-end bike shops. Procuring parts was a matter of both price and availability, since these bicycles are a small niche in the cycling community.

I modified practically everything but the frame, starting with the brakes for safety purposes. Cantilever brakes don’t have the strongest bite. Combine that with stiff, unergonomic levers, and I had to squeeze for my life every time I wanted to slow down. Once the brakes were sorted out with new levers, cables, and pads, the next thing to work on was the drivetrain.

The cogs at the rear couldn’t be swapped for larger ones due to the outdated 126mm rear-hub spacing, so I changed the crank to achieve the desired gearing. I wanted to keep the friction shifting since it’s part of the analog experience, but down-tube shifters aren’t the easiest to reach. Those were replaced with more accessible bar-end shifters.

Aside from the mechanical components, the cockpit was modified for a better fit. The drop bars were swapped for wider ones to accommodate a rando bag on the front rack. Instead of a leather Brooks, I opted for a synthetic leather saddle since it’s more affordable, comfortable, and easier to maintain.

The seat post was the most difficult part to find. Not only did it have to be 26.8mm in diameter (which is already rare), but it also needed to have minimal setback according to my bike fitter. Thankfully, the previous owner of the Eurasia had one that he was willing to sell to me.

After all the modifications, the Eurasia is still an underwhelming ride. It resembles more of a rugged road bike than a full-on gravel bike—but without any of the speed or the lightness at 13.5kg.

My hands are constantly busy operating the bar-end shifters, left and right. That’s not the most convenient way to change gears, but it makes the experience more immersive—sort of like driving with a stick shift.

Stopping power is decent, but will almost completely disappear in the wet. The ride isn’t bone-shattering, yet it also isn’t plush since the fenders could only take 700c by 32mm tires.

The Bridgestone is an old bike so it will never be as light, fast, or comfortable as a modern one. But it is unmatched in style and elegance. Despite its glaring weaknesses and limitations, I accomplished my first Laguna Loop with it. And when the time is right, I’d like to join my first Audax with this rando bike.

While I don’t regret getting the Bridgestone Eurasia, it isn’t the most practical choice. It isn’t portable like my trifold, nor as tough as my gravel bike. As much as I’d like to use it for commuting, there’s also the nagging feeling that I have to baby it because of the shiny silver parts.

I began the build brimming with hope, daydreaming of randonneuring with the classic bike on the European or the Japanese countryside during a fine summer’s day—only to grow disillusioned. It’s sad to say, but my expectations for the Eurasia ballooned along with its expenses.

What started at P30,000 ended up being worth more than P100,000. Looking back, the project was reasonable until I decided to splurge on über-expensive Velo Orange parts such as the crank, the hubs, and the fenders.

Cumulatively, those three components cost as much as the bike itself. Beyond that point, I felt the Eurasia had to be pristine and perfect to justify the spending. And this prevents me from simply enjoying the bike for what it is.

I even had a lofty plan to get the bike repainted with a navy blue frame and gold lugs. But sinking even more money will open the door to disappointment, and the stock paint is already gorgeous. So, I’ll just keep it as is.

What can you learn from this? If you’re thinking of building your own retro bike, one thing I can tell you is that, rationally speaking, the reasons against it outweigh those for it.

You’ll only end up spending more on something that will never perform as well as a modern bike. But if ever you take the plunge, the community of enthusiasts will be a godsend whether you need parts or advice.

More importantly, it’s not enough to know the ins and the outs such as the spec sheet and the parts list. You also need to have a realistic budget in mind and stick to it. Or else there won’t be any limit to your expenses (and your expectations).

Despite everything, I still appreciate vintage bikes, especially my Bridgestone Eurasia. They allow me to enjoy cycling more profoundly.

Comments