Taiwan is known for many things such as milk tea, semiconductors, and a tense relationship with the People’s Republic of China. I was blessed with the opportunity to visit its capital, Taipei, for almost a week. And being a mobility enthusiast, I looked forward to experiencing the transport system.

The moment I set foot in the city, two things immediately stood out: There were proper sidewalks, and the public transit was efficient. But those apply to any developed metropolis. What sets Taiwan apart is its cycling industry with Giant being considered the world’s largest bicycle manufacturer.

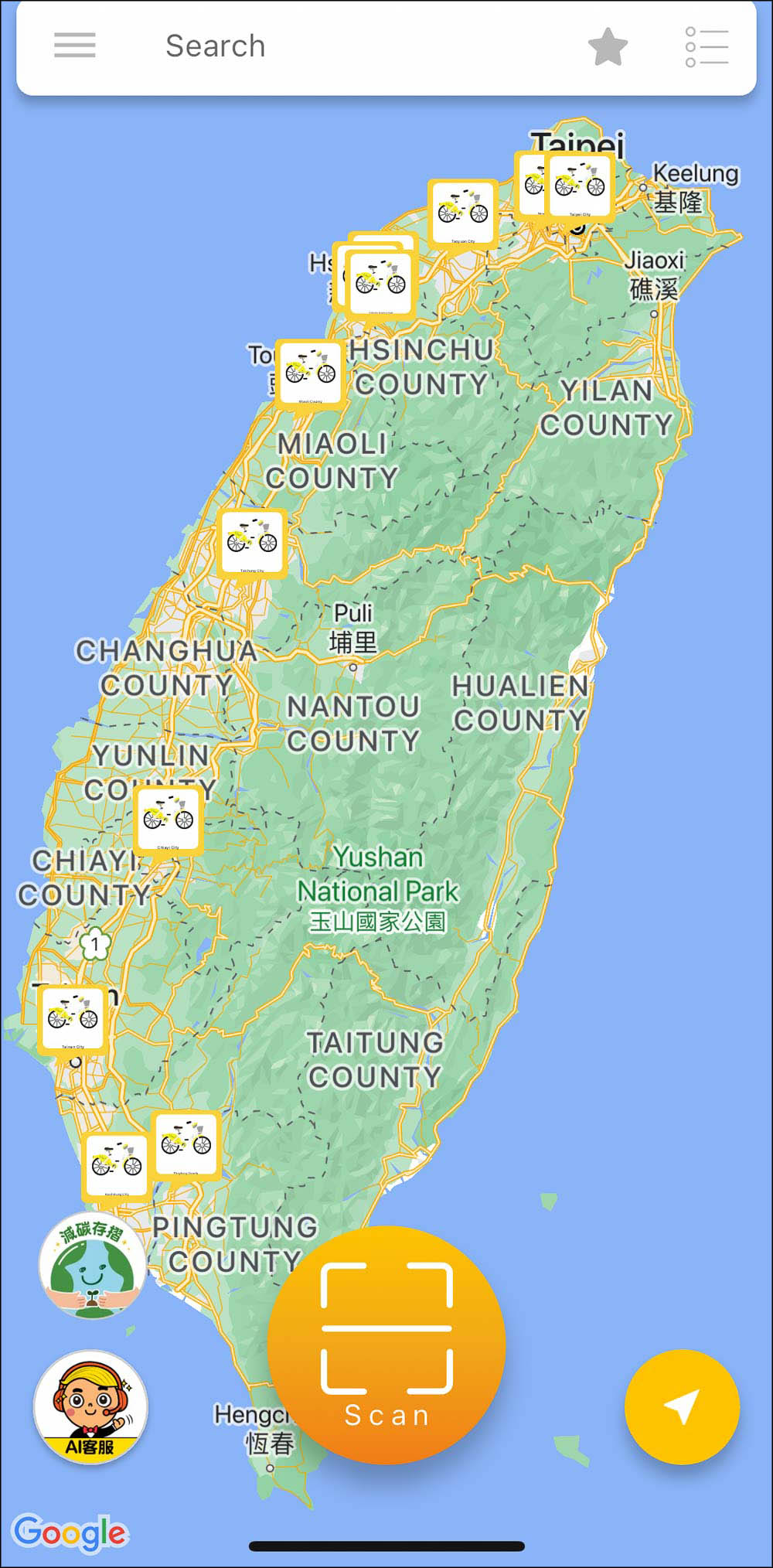

Knowing this, I was curious about what cycling is like around the city. And thanks to YouBike, there was no need to bring a bicycle. The government operates the ride-sharing system in collaboration with Giant.

You can’t miss it with the numerous users and the ubiquitous terminals. It’s as if people from all stages of life rent these bikes, whether they be youth going to school, employees commuting to work, or elderly doing errands.

To use YouBike, you’ll need either a credit card or a local SIM card and a stored-value card. In my case, I used the app to sign up by linking my local number with an EasyCard, which cost NT$100 (P176). Registration was done remotely, so I didn’t have to go to a store or kiosk to interact with someone.

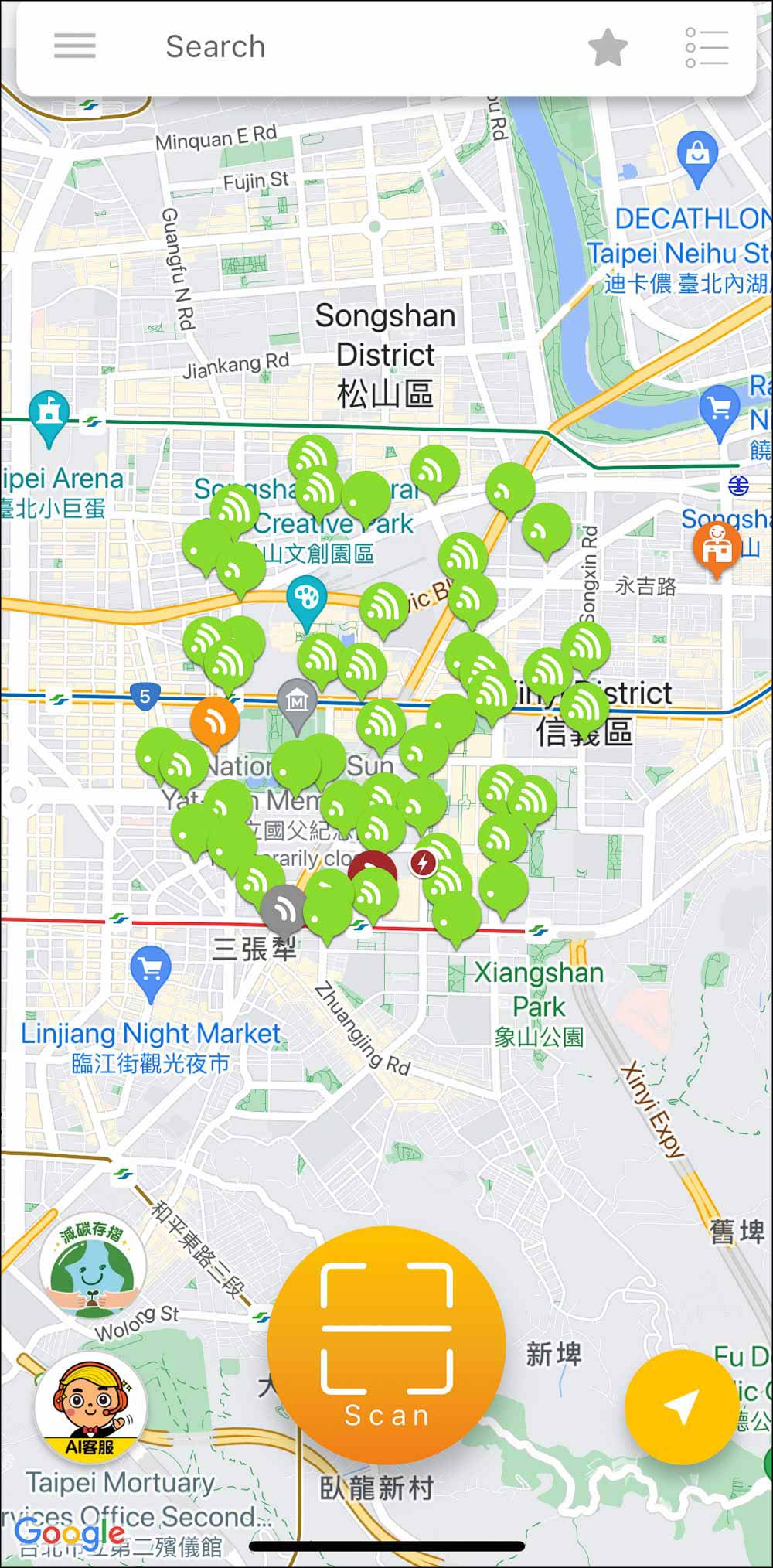

I originally encountered an error related to my password strength. But I discovered through Reddit that passwords have a strict character limit. With that solved, I only needed the app for locating specific stations.

As I said earlier, the terminals are practically everywhere. As long as people inhabit a place, you can be sure there’s a YouBike within walking distance. Google Maps is helpful when planning your trip as it gives you alternative cycling routes, similar to Waze.

Before renting a bike, check if the tires are inflated. Avoid units with a saddle facing backward since that means something’s wrong. To get riding, press the button, tap a loaded IC card, and pull the bike out of the terminal when it’s unlocked.

The rate starts at NT$10 (P18) for every 30 minutes (or a fraction thereof) for the first four hours. To give you perspective, an MRT ride starts at NT$20 (P36). Meanwhile, a 5km Uber ride was NT$350 (P618).

The beauty of this ride-sharing system is that it allows commuters to harmoniously blend different modes of mass transit to travel with efficiency and dignity. You can walk to a YouBike terminal, ride a bicycle to the bus stop or train station, and then rent a bike again or cover the last mile on foot.

Because there are viable alternatives, people are still mobile even if one mode is unavailable due to bad weather or a service interruption. There’s also no need to worry about parking or maintenance with YouBike’s system.

Cycling in a foreign country can be exciting yet frightening since each place has a different culture and behavior. Taiwan was no exception as I had to make some major adjustments.

For one, this was my first time bike-commuting without a helmet. However, I realized that wasn’t a problem because the streets were safe enough. Most locals don’t wear helmets, and the few that do are lycra-clad riders on speedy road bikes.

If you can walk the whole day as a tourist, then you are capable of biking around. That’s because cycling feels just as natural as walking—except you’re moving two to three times faster.

In Metro Manila, proper sidewalks are an exception. In Taipei, they are the norm—so you aren’t forced to toughen up and mingle with motor vehicles (also known as vehicular cycling).

Throughout the day, I waited for the moment when I’d find myself in the local counterpart of EDSA or C5. But that never happened.

Instead, imagine the widest walkways in BGC or Ayala Avenue (minus the underpasses), spread them across the city, and that’s pretty much how Taipei’s busiest thoroughfares felt like.

The sidewalk is your best friend since it is continuous and mostly unobstructed. The only thing to watch out for are pedestrians because you are more of a threat to them than they are to you.

Things are different in residential areas where there is no sidewalk. The narrow streets and the lower speed limit translate to calmer traffic.

Since pedestrians aren’t second-class road users, they’re given the same amount of time to cross an intersection as the green light for cars.

Speaking of intersections, you won’t have to climb any overpasses or footbridges as there is always ground-level crossing. And you don’t have to worry about getting right-hooked by drivers since they patiently yield at pedestrian crossings.

Turning left is a different story. Bicycles and scooters are usually required to do a two-stage turn (also known as the Copenhagen Left, a hook turn, or a box turn). That’s why there are white boxes in front of pedestrian crossings.

The few times I did go on the road were at stretches when the sidewalk got too crowded. And it was during those moments I saw the cracks in the street design. Without protected bike lanes on the road, I was up close and personal with motorists, who weren’t particularly respectful toward cyclists.

While Filipinos tend to drive dangerously and aggressively in a rat race to the red light, I felt that the Taiwanese motorists were just minding their own business amid the controlled chaos.

The fact that vehicular cycling is optional is a godsend when you just want to get around stress-free. But it would also be nice if the cycle paths were separated, so there’d be no need to weave around pedestrians mindlessly blocking the painted bike lane.

This is my second time bike-commuting abroad. I enjoyed biking in California more due to the scenic landscapes and the cold weather. But it’s no secret that a car is essential for living the American Dream.

In Taipei, I didn’t feel deprived of mobility. And the locals didn’t look miserable in their daily commute, too. As a tourist, cycling made the most sense as it allowed me to cover distance while taking in the sights—all while moving at my own pace and time.

This should go without saying, but if you just need to get from point A to B as quickly as possible, the subway will be faster. And if your luggage is too heavy, then you might want to spend more on a cab or Uber. Ultimately, what matters is that people have a choice.

Overall, I had a good time biking in Taipei. Yet, it is no Amsterdam. Despite the many bicycles Taiwan produces, you won’t find its capital on lists of the most bicycle-friendly cities in the world.

YouBike plays a big role in making bike-commuting viable, and the riverside bikeways are good if you need fresh air and a leisurely ride. However, more work needs to be done for the cycling infrastructure to be truly world-class.

There just happen to be proper sidewalks, reliable public transit, and drivers who respect pedestrians—the bare minimum for any decent transport system, really.

Still, traveling around Taipei is a world of difference compared to Metro Manila. “Move People, Not Cars” is a slogan you’d often hear from mobility advocates. And this rings true in the Taiwanese capital. Since the people there don’t have an unhealthy obsession with private cars, they can get around the city nicely without one.

Transportation there is diverse and inclusive. Aside from bicycles and scooters, I also saw e-bikes, e-scooters, electric kick scooters, and even an electric unicycle—the very things our authorities are trying to prohibit.

However, since the sidewalks there are accessible, there’s no need for those vehicles to go on the road. So instead of banning light EVs, perhaps the solution could start with making Metro Manila walkable.

If ever you find yourself traveling to Taiwan, I highly suggest you try out YouBike. Not only is it highly accessible and convenient, but it will also let you better appreciate the place and open your eyes to the wonders of bike-commuting and ride-sharing.

There’s a lot more to YouBike than what was covered here. If you want to learn more, you can visit its English website here.

Comments