According to Sigmund Freud, man tends to seek pleasure and avoid pain—the so-called “pleasure principle.” This is why normal people would rather sit for 30 minutes in an air-conditioned car to traverse a mile of gridlock rather than just walk and get it over with in 20 minutes. Taken to extremes, as humorously portrayed in WALL-E, people would probably spend most of their lives in a chair if it were at all possible, to the detriment of their health.

I wonder if Freud ever rode a bike. And not just for a simple ride to the village café that anyone could do, but for something epic. Something so difficult and so arduous that it would challenge his theory. Many times, I and many other cyclists have often asked ourselves the eternal question while suffering greatly in the middle of a gut-busting ascent:

“WHY AM I DOING THIS?!”

One fine, hellish day in mid-December, I asked this question many times while staring down at my bottom bracket, wishing for an extra gear, and pleading God for some welcome shade. I was at kilometer 70 or so, halfway up a very long and steep road, and not a drop of water left in my bidon.

Let’s rewind to a few weeks beforehand. In our old Fitness First Cycling group (long since retired from amateur racing, but we still kept in touch and rode on weekends), one guy (Maiqui Dayrit) asked who was game to ride to Sagada via the historic Bessang Pass. I raised my hand, as did a few others—and before long, we had a tidy little group that was looking forward to this bucket-list ride.

I had driven to Sagada before and always loved the views. I had also ridden my bike up to and around Baguio and the Cordilleras in the past, having joined a couple of road and mountain bike races, so I knew it would be extra challenging for a flatlander like me. These days, 30lb (13.6kg) over my optimal racing weight, and with an engine that doesn’t like to rev like it used to, racing up a climb isn’t even an option anymore.

Still, the prospect of climbing over 3,000m over three long climbs seemed intimidating but doable. To prepare for this trip, I spent three weeks of specific climbing in the Tagaytay area, going up and down the Talisay/Sampaloc road, and deliberately sticking to a heavy gear to simulate a steep gradient.

Even so, the stress of this kind of training was substantial. I had to call off some planned rides as my body called out for some much-needed recovery. The most climbing I did in a single ride totaled 1,600m of elevation gain, while the longest was nearly 160km—a proper century. It would have to do.

We started our ride from Tagudin, Ilocos Sur. The drive there from Metro Manila was largely uneventful except for the traffic buildup on NLEX in Bulacan. Once we’d made it to the SCTEX and the TPLEX, it was just straight ahead and trying not to fall asleep on this speed limit-enforced road.

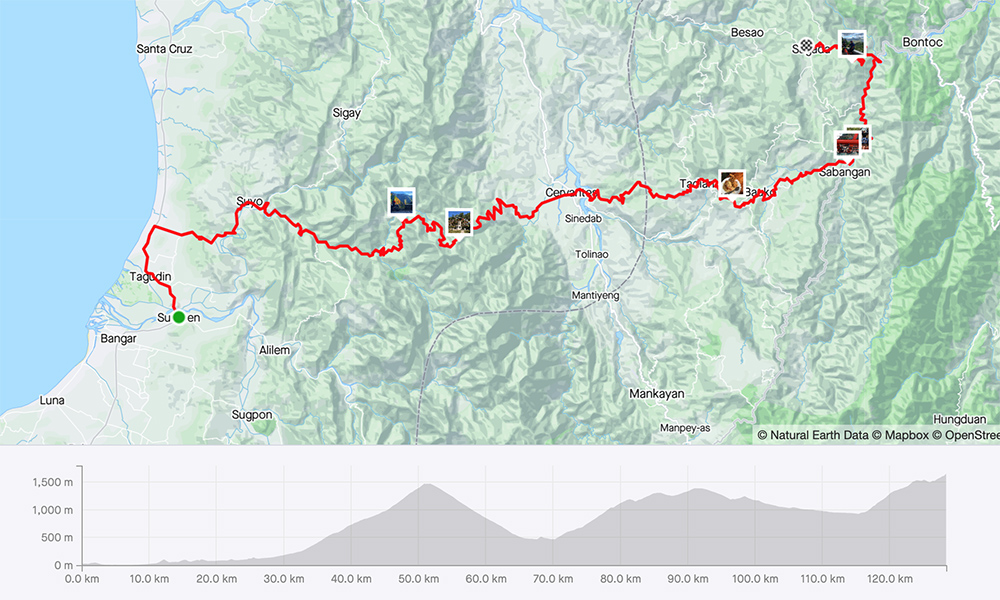

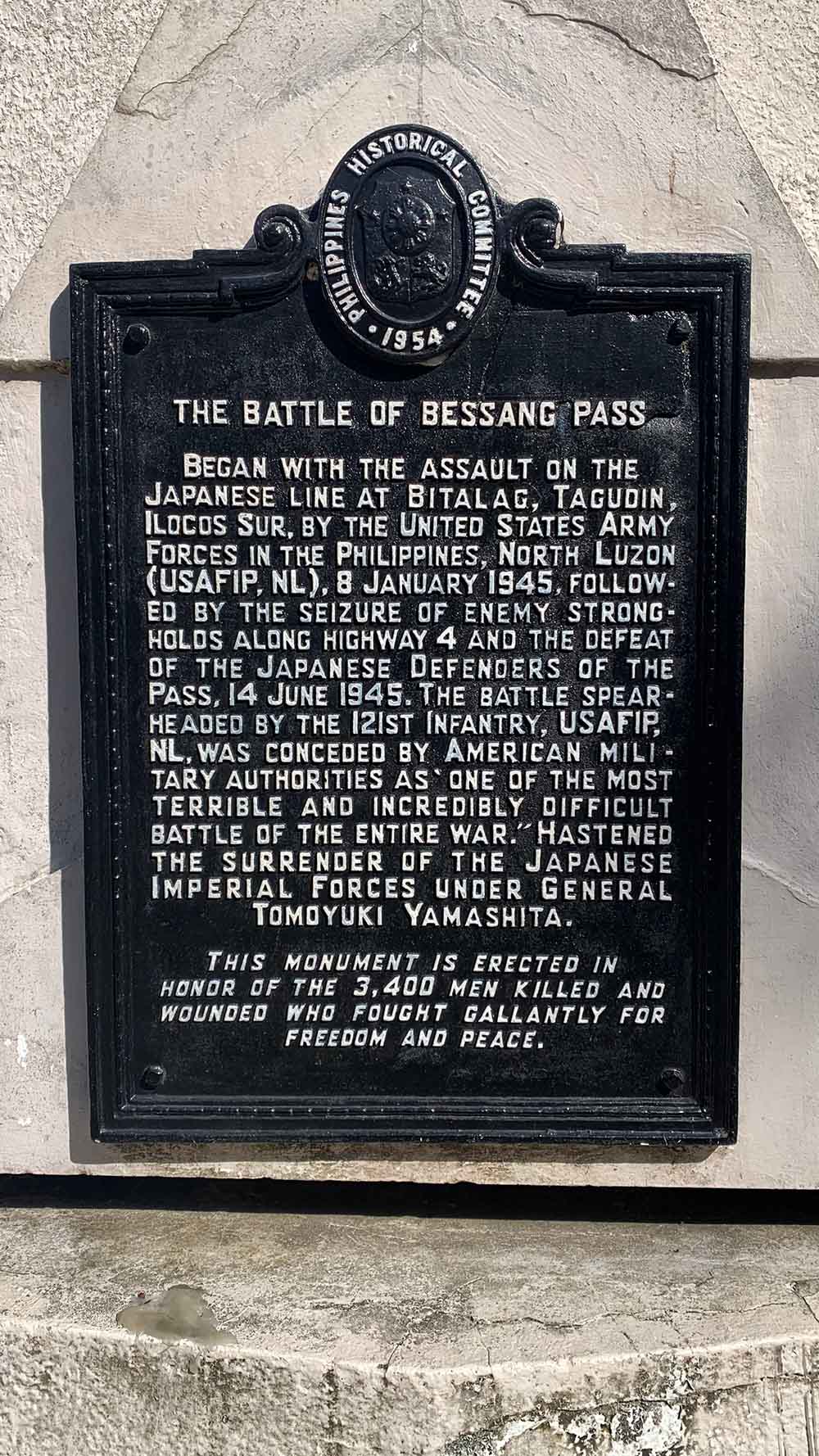

We were on our bikes by 5am the next day, with the first 10km being a flat road for a good warm-up. Once we got to Suyo, the ‘fun’ started. The first major climb of the day was the Bessang Pass, a narrow, winding, two-lane road that climbed 1,200m over 17.7km for an average gradient of 6.8%.

The spectacular views of forest-covered mountainsides and steep drop-offs made up for the difficulty, which pitched up to around 8-10% over the last 5km. Unlike most of my companions, I hadn’t had the time to equip my bike with shorter gearing than the stock 34T-by-34T (1:1) combination.

It was actually okay for shorter, steep climbs, but anything longer than several hundred meters and my cadence dropped to sub-60rpm, mashing the gears. On the flip side, this also forced me to calm down and focus on the muscle contraction/extension phase rather than going for a high cadence/high heart rate approach.

We reached the historical monument at the top in a little over two hours—decent for first-timers—and took a half-hour break to eat, take pictures, and regroup. I also stole a nap.

From the top of the pass, we now took a vertiginous descent to the next climb, the 7.58km road from Aluling to Bunga.

The gradient was only 6.3%, but with the road directly facing the sun, the midday heat took its toll on all of us. On the steep switchbacks with their 11-12% gradients, I began entertaining the thought of calling it a day and taking a ride in our Support and Gear (SAG) truck provided by Ride Out Manila’s Bush Sayson. Except, he had gone ahead in search of half of our group that had taken another route, and now it was every man for himself on that unforgiving road. I could swear that road was twice the advertised distance!

Eventually, we regrouped with the truck and the other riders for a much-needed late lunch in the town of Bauko.

By now we were at kilometer 100, and our ride leader (Atty. Aldean Lim) told us the most exciting news: The final push to Sagada was 12km, with around 1,000m elevation gain. That is an 8.3% average. Oh, Lord! We are going to have a long conversation on the way up this monster.

From the moment we made the first critical turn to the town, it was an absolute nightmare of a climb. We’d been on our bikes for around seven hours now, and the fatigue combined with the sheer gradient put us all deep in the hurt locker.

We ground our way up in ones and twos, and the few motorists who were also on the road that day gave us a lot of leeway as we zigged and zagged to somehow lessen the gradient. Just to taunt me, my cyclocomputer kept going on auto-pause as my speed was now down to less than 5km/h at some points. I’d never ridden so slowly in my life until that day.

By the midpoint, we were faced with several ramps of 16%, and only the fact that we were so close to finishing kept me going.

We finally rolled into Sagada at around 5pm, just in time to enjoy the beautiful sunset and some much-deserved drinks at Sagada Cellar Door. There, the host Andrew Chinalpan regaled us with tales of some even harder climbs in the area while plying us with some of his fantastic craft beer and liqueurs.

We finished the day with 128km on the cyclocomp, and a grand total of 3,619m elevation gain.

Total riding time was 8:25, but the actual time including stops was closer to 12 hours. We’d done the equivalent of a monster stage of the Tour de France or the Giro d’Italia, except the pros do this sort of thing in less than half the time it took us. At least we eat better.

So, back to Freud. If man is predisposed to pleasure, why on earth would he subject himself to so much suffering on a bike ride?

You have to ride a bike to know the answer. It’s only after enduring so much suffering that one gets a most unique pleasure. It’s not from making a ton of money, or enjoying good sex, or even a delicious meal. It’s the satisfaction of finishing something never done before, something few people will ever get to try—something that few will ever understand. An accomplishment that you have to work your butt off is its own reward.

At the end of the day, it’s now about how heavy or light you are. It’s not about how fancy or shitty your bike is. It’s not even about all that baggage you carry around in your head if you’ve got a day job and adult responsibilities.

It’s all about finishing the damn ride and learning a little bit more about yourself along the way. You conquer a fear of climbing something like this, and you’ll be ready to face another challenge down the road.

Comments